Josephus

Flavius Josephus | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 37 AD[1] |

| Died | c. 100 AD[1] (aged 62–63) |

| Children | 5 sons |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Hellenistic Judaism |

| Main interests | |

| Notable works | |

| Influenced | |

Titus Flavius Josephus (/dʒoʊˈsiːfəs/;[3] Greek: Ἰώσηπος, Iṓsēpos; Hebrew: יוֹסֵף בֶּן מַתִּתְיָהוּ, Yōsēf ben Mattīṯyāhū;[4][5] c. 37 – c. 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for The Jewish War, who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly descent and a mother who claimed royal ancestry.

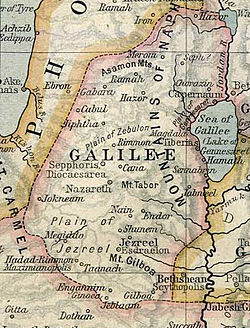

He initially fought against the Romans during the First Jewish–Roman War as head of Jewish forces in Galilee, until surrendering in 67 AD to Roman forces led by Vespasian after the six-week siege of Yodfat. Josephus claimed the Jewish Messianic prophecies that initiated the First Jewish–Roman War made reference to Vespasian becoming Emperor of Rome. In response, Vespasian decided to keep Josephus as a slave and presumably interpreter. After Vespasian became Emperor in 69 AD, he granted Josephus his freedom, at which time Josephus assumed the emperor's family name of Flavius.[6]

Flavius Josephus fully defected to the Roman side and was granted Roman citizenship. He became an advisor and friend of Vespasian's son Titus, serving as his translator when Titus led the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD. Since the siege proved ineffective at stopping the Jewish revolt, the city's pillaging and the looting and destruction of Herod's Temple (Second Temple) soon followed.

Josephus recorded the First Jewish–Roman War (66–70 AD), including the siege of Masada. His most important works were The Jewish War (c. 75) and Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94).[7] The Jewish War recounts the Jewish revolt against Roman occupation. Antiquities of the Jews recounts the history of the world from a Jewish perspective for an ostensibly Greek and Roman audience. These works provide valuable insight into first century Judaism and the background of Early Christianity.[7] Josephus's works are the chief source next to the Bible for the history and antiquity of ancient Palestine, and provide a significant and independent extra-Biblical account of such figures as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, John the Baptist, James the Just, and possibly Jesus of Nazareth.

Biography[edit]

Josephus was born into one of Jerusalem's elite families.[8] He was the second-born son of Matthias, a Jewish priest. His older full-blooded brother was also, like his father, called Matthias.[9] Their mother was an aristocratic woman who was descended from the royal and formerly ruling Hasmonean dynasty.[10] Josephus's paternal grandparents were a man also named Josephus and his wife—an unnamed Hebrew noblewoman—distant relatives of each other.[11] Josephus's family was wealthy. He descended through his father from the priestly order of the Jehoiarib, which was the first of the 24 orders of priests in the Temple in Jerusalem.[12] Josephus was a descendant of the High Priest of Israel Jonathan Apphus.[12] He was raised in Jerusalem and educated alongside his brother.[13]

In his mid twenties, he traveled to negotiate with Emperor Nero for the release of some Jewish priests.[14] Upon his return to Jerusalem, at the outbreak of the First Jewish–Roman War, Josephus was appointed the military governor of Galilee.[15] His arrival in Galilee, however, was fraught with internal division: the inhabitants of Sepphoris and Tiberias opting to maintain peace with the Romans; the people of Sepphoris enlisting the help of the Roman army to protect their city,[16] while the people of Tiberias appealing to King Agrippa's forces to protect them from the insurgents.[17]

Josephus also contended with John of Gischala who had also set his sight over the control of Galilee. Like Josephus, John had amassed to himself a large band of supporters from Gischala (Gush Halab) and Gabara,[a] including the support of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem.[21] Meanwhile, Josephus fortified several towns and villages in Lower Galilee, among which were Tiberias, Bersabe, Selamin, Japha, and Tarichaea, in anticipation of a Roman onslaught.[22] In Upper Galilee, he fortified the towns of Jamnith, Seph, Mero, and Achabare, among other places.[22] Josephus, with the Galileans under his command, managed to bring both Sepphoris and Tiberias into subjection,[16] but was eventually forced to relinquish his hold on Sepphoris by the arrival of Roman forces under Placidus the tribune and later by Vespasian himself. Josephus first engaged the Roman army at a village called Garis, where he launched an attack against Sepphoris a second time, before being repulsed.[23] At length, he resisted the Roman army in its siege of Yodfat (Jotapata) until it fell to the Roman army in the lunar month of Tammuz, in the thirteenth year of Nero's reign.

After the Jewish garrison of Yodfat fell under siege, the Romans invaded, killing thousands; the survivors committed suicide. According to Josephus, he was trapped in a cave with 40 of his companions in July 67 AD. The Romans (commanded by Flavius Vespasian and his son Titus, both subsequently Roman emperors) asked the group to surrender, but they refused. According to Josephus's account, he suggested a method of collective suicide;[24] they drew lots and killed each other, one by one, and Josephus happened to be one of two men that were left who surrendered to the Roman forces and became prisoners.[b] In 69 AD, Josephus was released.[26] According to his account, he acted as a negotiator with the defenders during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD, during which time his parents were held as hostages by Simon bar Giora.[27]

While being confined at Yodfat (Jotapata), Josephus claimed to have experienced a divine revelation that later led to his speech predicting Vespasian would become emperor. After the prediction came true, he was released by Vespasian, who considered his gift of prophecy to be divine. Josephus wrote that his revelation had taught him three things: that God, the creator of the Jewish people, had decided to "punish" them; that "fortune" had been given to the Romans; and that God had chosen him "to announce the things that are to come".[28][29][30] To many Jews, such claims were simply self-serving.[31]

In 71 AD, he went to Rome in the entourage of Titus, becoming a Roman citizen and client of the ruling Flavian dynasty (hence he is often referred to as Flavius Josephus). In addition to Roman citizenship, he was granted accommodation in conquered Judaea and a pension. While in Rome and under Flavian patronage, Josephus wrote all of his known works. Although he uses "Josephus", he appears to have taken the Roman praenomen Titus and nomen Flavius from his patrons.[32]

Vespasian arranged for Josephus to marry a captured Jewish woman, whom he later divorced. About 71 AD, Josephus married an Alexandrian Jewish woman as his third wife. They had three sons, of whom only Flavius Hyrcanus survived childhood. Josephus later divorced his third wife. Around 75 AD, he married his fourth wife, a Greek Jewish woman from Crete, who was a member of a distinguished family. They had a happy married life and two sons, Flavius Justus and Flavius Simonides Agrippa.

Josephus's life story remains ambiguous. He was described by Harris in 1985 as a law-observant Jew who believed in the compatibility of Judaism and Graeco-Roman thought, commonly referred to as Hellenistic Judaism.[7] Before the 19th century, the scholar Nitsa Ben-Ari notes that his work was banned as those of a traitor, whose work was not to be studied or translated into Hebrew.[33] His critics were never satisfied as to why he failed to commit suicide in Galilee, and after his capture, accepted the patronage of Romans.

Scholarship and impact on history[edit]

The works of Josephus provide crucial information about the First Jewish-Roman War and also represent important literary source material for understanding the context of the Dead Sea Scrolls and late Temple Judaism.

Josephan scholarship in the 19th and early 20th centuries took an interest in Josephus's relationship to the sect of the Pharisees.[citation needed] It consistently portrayed him as a member of the sect and as a traitor to the Jewish nation—a view which became known as the classical concept of Josephus.[34] In the mid-20th century a new generation of scholars[who?] challenged this view and formulated the modern concept of Josephus. They consider him a Pharisee but restore his reputation in part as patriot and a historian of some standing. In his 1991 book, Steve Mason argued that Josephus was not a Pharisee but an orthodox Aristocrat-Priest who became associated with the philosophical school of the Pharisees as a matter of deference, and not by willing association.[35]

Impact on history and archaeology[edit]

The works of Josephus include useful material for historians about individuals, groups, customs, and geographical places. However, modern historians have been cautious of taking his writings at face value. For example, Carl Ritter, in his highly influential Erdkunde in the 1840s, wrote in a review of authorities on the ancient geography of the region:

Outside of the Scriptures, Josephus holds the first and the only place among the native authors of Judaea; for Philo of Alexandria, the later Talmud, and other authorities, are of little service in understanding the geography of the country. Josephus is, however, to be used with great care. As a Jewish scholar, as an officer of Galilee, as a military man, and a person of great experience in everything belonging to his own nation, he attained to that remarkable familiarity with his country in every part, which his antiquarian researches so abundantly evince. But he was controlled by political motives: his great purpose was to bring his people, the despised Jewish race, into honour with the Greeks and Romans; and this purpose underlay every sentence, and filled his history with distortions and exaggerations.[36]

Josephus mentions that in his day there were 240 towns and villages scattered across Upper and Lower Galilee,[37] some of which he names. Josephus' works are the primary source for the chain of Jewish high priests during the Second Temple period. A few of the Jewish customs named by him include the practice of hanging a linen curtain at the entrance to one's house,[38] and the Jewish custom to partake of a Sabbath-day's meal around the sixth-hour of the day (at noon).[39] He notes also that it was permissible for Jewish men to marry many wives (polygamy).[40] His writings provide a significant, extra-Biblical account of the post-Exilic period of the Maccabees, the Hasmonean dynasty, and the rise of Herod the Great. He also describes the Sadducees, the Pharisees and Essenes, the Herodian Temple, Quirinius' census and the Zealots, and such figures as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, Agrippa I and Agrippa II, John the Baptist, James the brother of Jesus, and Jesus.[41] Josephus represents an important source for studies of immediate post-Temple Judaism and the context of early Christianity.

A careful reading of Josephus's writings and years of excavation allowed Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist from Hebrew University, to discover what he considered to be the location of Herod's Tomb, after searching for 35 years.[42] It was above aqueducts and pools, at a flattened desert site, halfway up the hill to the Herodium, 12 km south of Jerusalem—as described in Josephus's writings.[43] In October 2013, archaeologists Joseph Patrich and Benjamin Arubas challenged the identification of the tomb as that of Herod.[44] According to Patrich and Arubas, the tomb is too modest to be Herod's and has several unlikely features.[44] Roi Porat, who replaced Netzer as excavation leader after the latter's death, stood by the identification.[44]

Josephus's writings provide the first-known source for many stories considered as Biblical history, despite not being found in the Bible or related material. These include Ishmael as the founder of the Arabs,[45] the connection of "Semites", "Hamites" and "Japhetites" to the classical nations of the world, and the story of the siege of Masada.[46]

Josephus's original audience[edit]

Scholars debate about Josephus's intended audience. For example, Antiquities of the Jews could be written for Jews—"a few scholars from Laqueur onward have suggested that Josephus must have written primarily for fellow-Jews (if also secondarily for Gentiles). The most common motive suggested is repentance: in later life he felt so badly about the traitorous War that he needed to demonstrate … his loyalty to Jewish history, law and culture."[47] However, Josephus's "countless incidental remarks explaining basic Judean language, customs and laws … assume a Gentile audience. He does not expect his first hearers to know anything about the laws or Judean origins."[48] The issue of who would read this multi-volume work is unresolved. Other possible motives for writing Antiquities could be to dispel the misrepresentation of Jewish origins[49] or as an apologetic to Greek cities of the Diaspora in order to protect Jews and to Roman authorities to garner their support for the Jews facing persecution.[50]

Literary influence and translations[edit]

Josephus was a very popular writer with Christians in the 4th century and beyond as an independent witness to the events before, during, and after the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Josephus was always accessible in the Greek-reading Eastern Mediterranean. His works were translated into Latin, but often in abbreviated form such as Pseudo-Hegesippus's 4th century Latin version of The Jewish War (Bellum Judaicum). Christian interest in The Jewish War was largely out of interest in the downfall of the Jews and the Second Temple, which was widely considered divine punishment for the crime of killing Jesus. Improvements in printing technology (the Gutenberg Press) led to his works receiving a number of new translations into the vernacular languages of Europe, generally based on the Latin versions. Only in 1544 did a version of the standard Greek text become available in French, edited by the Dutch humanist Arnoldus Arlenius. The first English translation, by Thomas Lodge, appeared in 1602, with subsequent editions appearing throughout the 17th century. The 1544 Greek edition formed the basis of the 1732 English translation by William Whiston, which achieved enormous popularity in the English-speaking world. It was often the book—after the Bible—that Christians most frequently owned. Whiston claimed that certain works by Josephus had a similar style to the Epistles of St. Paul.[51][52] Later editions of the Greek text include that of Benedikt Niese, who made a detailed examination of all the available manuscripts, mainly from France and Spain. Henry St. John Thackeray and successors such as Ralph Marcus used Niese's version for the Loeb Classical Library edition widely used today.

On the Jewish side, Josephus was far more obscure, as he was perceived as a traitor. Rabbinical writings for a millennium after his death (e.g. the Mishnah) almost never call out Josephus by name, although they sometimes tell parallel tales of the same events that Josephus narrated. An Italian Jew writing in the 10th century indirectly brought Josephus back to prominence among Jews: he authored the Yosippon, which paraphrases Pseudo-Hegesippus's Latin version of The Jewish War, a Latin version of Antiquities, as well as other works. The epitomist also adds in their own snippets of history at times. Jews generally distrusted Christian translations of Josephus until the Haskalah ("Jewish Enlightenment") in the 19th century, when sufficiently "neutral" vernacular language translations were made. Kalman Schulman finally created a translation of the Greek text of Josephus into Hebrew in 1863, although many rabbis continued to prefer the Yosippon version. By the 20th century, Jewish attitudes toward Josephus had softened, as he gave the Jews a respectable place in classical history. Various parts of his work were reinterpreted as more inspiring and favorable to the Jews than the Renaissance translations by Christians had been. Notably, the last stand at Masada (described in The Jewish War), which had been interpreted as insane and fanatical in earlier eras, received a more positive reinterpretation as an inspiring call to action in this period.[52][53]

The standard editio maior of the various Greek manuscripts is that of Benedictus Niese, published 1885–95. The text of Antiquities is damaged in some places. In the Life, Niese follows mainly manuscript P, but refers also to AMW and R. Henry St. John Thackeray for the Loeb Classical Library has a Greek text also mainly dependent on P.[citation needed] André Pelletier edited a new Greek text for his translation of Life. The ongoing Münsteraner Josephus-Ausgabe of Münster University will provide a new critical apparatus. There also exist late Old Slavonic translations of the Greek, but these contain a large number of Christian interpolations.[54]

Modern analysis[edit]

In modern times, the writings of Josephus have been frequently critiqued as inaccurate, embellished and coloured by Josephus' partial take on events he was involved in. Author Joseph Raymond calls Josephus "the Jewish Benedict Arnold" for betraying his own troops at Jotapata,[55] while historian Mary Smallwood, in the introduction to the translation of The Jewish War by G. A. Williamson, writes:

[Josephus] was conceited, not only about his own learning, but also about the opinions held of him as commander both by the Galileans and by the Romans; he was guilty of shocking duplicity at Jotapata, saving himself by sacrifice of his companions; he was too naive to see how he stood condemned out of his own mouth for his conduct, and yet no words were too harsh when he was blackening his opponents; and after landing, however involuntarily, in the Roman camp, he turned his captivity to his own advantage, and benefited for the rest of his days from his change of side.[56]

Historiography and Josephus[edit]

In the Preface to Jewish Wars, Josephus criticizes historians who misrepresent the events of the Jewish–Roman War, writing that "they have a mind to demonstrate the greatness of the Romans, while they still diminish and lessen the actions of the Jews."[57] Josephus states that his intention is to correct this method but that he "will not go to the other extreme … [and] will prosecute the actions of both parties with accuracy."[58] Josephus suggests his method will not be wholly objective by saying he will be unable to contain his lamentations in transcribing these events; to illustrate this will have little effect on his historiography, Josephus suggests, "But if any one be inflexible in his censures of me, let him attribute the facts themselves to the historical part, and the lamentations to the writer himself only."[58]

His preface to Antiquities offers his opinion early on, saying, "Upon the whole, a man that will peruse this history, may principally learn from it, that all events succeed well, even to an incredible degree, and the reward of felicity is proposed by God."[59] After inserting this attitude, Josephus contradicts himself: "I shall accurately describe what is contained in our records, in the order of time that belongs to them … without adding any thing to what is therein contained, or taking away any thing therefrom."[59] He notes the difference between history and philosophy by saying, "[T]hose that read my book may wonder how it comes to pass, that my discourse, which promises an account of laws and historical facts, contains so much of philosophy."[60]

In both works, Josephus emphasizes that accuracy is crucial to historiography. Louis H. Feldman notes that in Wars, Josephus commits himself to critical historiography, but in Antiquities, Josephus shifts to rhetorical historiography, which was the norm of his time.[61] Feldman notes further that it is significant that Josephus called his later work "Antiquities" (literally, archaeology) rather than history; in the Hellenistic period, archaeology meant either "history from the origins or archaic history."[62] Thus, his title implies a Jewish peoples' history from their origins until the time he wrote. This distinction is significant to Feldman, because "in ancient times, historians were expected to write in chronological order," while "antiquarians wrote in a systematic order, proceeding topically and logically" and included all relevant material for their subject.[62] Antiquarians moved beyond political history to include institutions and religious and private life.[63] Josephus does offer this wider perspective in Antiquities.

To compare his historiography with another ancient historian, consider Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Feldman lists these similarities: "Dionysius in praising Rome and Josephus in praising Jews adopt same pattern; both often moralize and psychologize and stress piety and role of divine providence; and the parallels between … Dionysius's account of deaths of Aeneas and Romulus and Josephus's description of the death of Moses are striking."[63]

Works[edit]

The works of Josephus are major sources of our understanding of Jewish life and history during the first century.[64]

- (c. 75) War of the Jews, The Jewish War, Jewish Wars, or History of the Jewish War (commonly abbreviated JW, BJ or War)

- (c. 94) Antiquities of the Jews, Jewish Antiquities, or Antiquities of the Jews/Jewish Archeology (frequently abbreviated AJ, AotJ or Ant. or Antiq.)

- (c. 97) Flavius Josephus Against Apion, Against Apion, Contra Apionem, or Against the Greeks, on the antiquity of the Jewish people (usually abbreviated CA)

- (c. 99) The Life of Flavius Josephus, or Autobiography of Flavius Josephus (abbreviated Life or Vita)

The Jewish War[edit]

His first work in Rome was an account of the Jewish War, addressed to certain "upper barbarians"—usually thought to be the Jewish community in Mesopotamia—in his "paternal tongue" (War I.3), arguably the Western Aramaic language. In 78 AD he finished a seven-volume account in Greek known as the Jewish War (Latin Bellum Judaicum or De Bello Judaico). It starts with the period of the Maccabees and concludes with accounts of the fall of Jerusalem, and the subsequent fall of the fortresses of Herodion, Macharont and Masada and the Roman victory celebrations in Rome, the mopping-up operations, Roman military operations elsewhere in the empire and the uprising in Cyrene. Together with the account in his Life of some of the same events, it also provides the reader with an overview of Josephus's own part in the events since his return to Jerusalem from a brief visit to Rome in the early 60s (Life 13–17).[65]

In the wake of the suppression of the Jewish revolt, Josephus would have witnessed the marches of Titus's triumphant legions leading their Jewish captives, and carrying treasures from the despoiled Temple in Jerusalem. It was against this background that Josephus wrote his War, claiming to be countering anti-Judean accounts. He disputes the claim[citation needed] that the Jews served a defeated God and were naturally hostile to Roman civilization. Rather, he blames the Jewish War on what he calls "unrepresentative and over-zealous fanatics" among the Jews, who led the masses away from their traditional aristocratic leaders (like himself), with disastrous results. For example, Josephus writes that "Simon [bar Giora] was a greater terror to the people than the Romans themselves."[66] Josephus also blames some of the Roman governors of Judea, representing them as corrupt and incompetent administrators. According to Josephus, the traditional Jew was, should be, and can be a loyal and peace-loving citizen. Jews can, and historically have, accepted Rome's hegemony precisely because their faith declares that God himself gives empires their power.[67]

Jewish Antiquities[edit]

The next work by Josephus is his twenty-one volume Antiquities of the Jews, completed during the last year of the reign of the Emperor Flavius Domitian, around 93 or 94 AD. In expounding Jewish history, law and custom, he is entering into many philosophical debates current in Rome at that time. Again he offers an apologia for the antiquity and universal significance of the Jewish people. Josephus claims to be writing this history because he "saw that others perverted the truth of those actions in their writings,"[68] those writings being the history of the Jews. In terms of some of his sources for the project, Josephus says that he drew from and "interpreted out of the Hebrew Scriptures"[69] and that he was an eyewitness to the wars between the Jews and the Romans,[68] which were earlier recounted in Jewish Wars.

He outlines Jewish history beginning with the creation, as passed down through Jewish historical tradition. Abraham taught science to the Egyptians, who, in turn, taught the Greeks.[70] Moses set up a senatorial priestly aristocracy, which, like that of Rome, resisted monarchy. The great figures of the Tanakh are presented as ideal philosopher-leaders. He includes an autobiographical appendix defending his conduct at the end of the war when he cooperated with the Roman forces.

Louis H. Feldman outlines the difference between calling this work Antiquities of the Jews instead of History of the Jews. Although Josephus says that he describes the events contained in Antiquities "in the order of time that belongs to them,"[59] Feldman argues that Josephus "aimed to organize [his] material systematically rather than chronologically" and had a scope that "ranged far beyond mere political history to political institutions, religious and private life."[63]

Against Apion[edit]

Josephus's Against Apion is a two-volume defence of Judaism as classical religion and philosophy, stressing its antiquity, as opposed to what Josephus claimed was the relatively more recent tradition of the Greeks. Some anti-Judaic allegations ascribed by Josephus to the Greek writer Apion and myths accredited to Manetho are also addressed.

Spurious works[edit]

- (date unknown) Josephus's Discourse to the Greeks concerning Hades (spurious; adaptation of "Against Plato, on the Cause of the Universe" by Hippolytus of Rome)

See also[edit]

- Josephus on Jesus

- Josephus problem – a mathematical problem named after Josephus

- Josippon

- Pseudo-Philo

Notes and references[edit]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ A large village in Galilee during the 1st century AD, located to the north of Nazareth. In antiquity, the town was called "Garaba", but in Josephus' historical works of antiquity, the town is mentioned by its Greek corruption, "Gabara".[18][19][20]

- ^ This method as a mathematical problem is referred to as the Josephus problem, or Roman roulette.[25]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Mason 2000.

- ^ Antiquities of the Jews, xviii.8, § 1, Whiston's translation (online)

- ^ "Josephus". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins Publishers.

- ^ "Flavius Josephus". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Josephus Flavius". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Simon Claude Mimouni, Le Judaïsme ancien du VIe siècle avant notre ère au IIIe siècle de notre ère : Des prêtres aux rabbins, Paris, P.U.F., coll. « Nouvelle Clio », 2012, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Harris 1985.

- ^ Goodman, Martin (2007). Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilisations. Penguin Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-713-99447-6.

Josephus was born into the ruling elite of Jerusalem

- ^ Mason 2000, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Nodet 1997, p. 250.

- ^ "Josephus Lineage" (PDF). History of the Daughters (Fourth ed.). Sonoma, California: L P Publishing. December 2012. pp. 349–350.

- ^ a b Schürer 1973, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Mason 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Josephus, Vita § 3

- ^ Goldberg, G. J. "The Life of Flavius Josephus". Josephus.org. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ^ a b Josephus, Vita, § 67

- ^ Josephus, Vita, § 68

- ^ Klausner, J. (1934). "Qobetz". Journal of the Jewish Palestinian Exploration Society (in Hebrew). 3: 261–263.

- ^ Rappaport, Uriel (2013). John of Gischala, from the mountains of Galilee to the walls of Jerusalem. p. 44 [note 2].

- ^ Safrai, Ze'ev (1985). The Galilee in the time of the Mishna and Talmud (in Hebrew) (2nd ed.). Jerusalem. pp. 59–62.

- ^ Josephus, Vita, § 25; § 38; Josephus (1926). "The Life of Josephus". doi:10.4159/DLCL.josephus-life.1926. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required) - ^ a b Josephus, Vita, § 37

- ^ Josephus, Vita, § 71

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War. Book 3, Chapter 8, par. 7

- ^ Cf. this example, Roman Roulette. Archived February 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jewish War IV.622–629

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War (5.13.1. and 5.13.3.)

- ^ Gray 1993, pp. 35–38.

- ^ Aune 1991, p. 140.

- ^ Gnuse 1996, pp. 136–142.

- ^ Goodman, Martin (2007). Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilisations. Penguin Books. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-713-99447-6.

Later generations of Jews have been inclined to treat such claims as self-serving

- ^ Attested by the third-century Church theologian Origen (Comm. Matt. 10.17).

- ^ Ben-Ari, Nitsa (2003). "The double conversion of Ben-Hur: a case of manipulative translation" (PDF). Target. 14 (2): 263–301. doi:10.1075/target.14.2.05ben. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

The converts themselves were banned from society as outcasts and so was their historiographic work or, in the more popular historical novels, their literary counterparts. Josephus Flavius, formerly Yosef Ben Matityahu (34–95), had been shunned, then banned as a traitor.

- ^ Millard 1997, p. 306.

- ^ Mason, Steve (April 2003). "Flavius Josephus and the Pharisees". The Bible and Interpretation. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ^ Ritter, C. (1866). The comparative geographie of Palestine and the Sinaitic Peninsula. T. & T. Clark.

- ^ Josephus, Vita § 45

- ^ Flavius Josephus, The Works of Flavius Josephus. Translated by William Whiston, A.M. Auburn and Buffalo. John E. Beardsley: 1895, s.v. Antiquities 3.6.4. (3.122). After describing the curtain that hung in the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, Josephus adds: "…Whence that custom of ours is derived, of having a fine linen veil, after the temple has been built, to be drawn over the entrances."

- ^ Josephus, Vita § 54

- ^ Flavius Josephus, The Works of Flavius Josephus. Translated by William Whiston, A.M. Auburn and Buffalo. John E. Beardsley: 1895, s.v. The Jewish War 1.24.2 (end) (1.473).

- ^ Whealey, Alice (2003). Josephus on Jesus: The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times. Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8204-5241-8.

In the sixteenth century the authenticity of the text [Testimonium Flavianum] was publicly challenged, launching a controversy that has still not been resolved today

- ^ Kraft, Dina (May 9, 2007). "Archaeologist Says Remnants of King Herod's Tomb Are Found". NY Times. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Murphy 2008, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Hasson, Nir (October 11, 2013). "Archaeological stunner: Not Herod's Tomb after all?". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Millar, Fergus, 2006. ‘Hagar, Ishmael, Josephus, and the origins of Islam’. In Fergus Millar, Hannah H. Cotton, and Guy MacLean Rogers, Rome, the Greek World and the East. Vol. 3. The Greek World, the Jews and the East, 351–377. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ The Myth of Masada: How Reliable Was Josephus, Anyway?: "The only source we have for the story of Masada, and numerous other reported events from the time, is the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, author of the book “The Jewish War”."

- ^ Mason 1998, p. 66.

- ^ Mason 1998, p. 67.

- ^ Mason 1998, p. 68.

- ^ Mason 1998, p. 70.

- ^ Maier 1999, p. 1070.

- ^ a b Josephus, Flavius (2017) [c. 75]. The Jewish War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. xxix–xxxv.. Information is from the Introduction, by Martin Goodman.

- ^ Rajak, Tessa (2016). "Josephus, Jewish Resistance, and the Masada Myth". In Collins, John J.; Manning, J. G. (eds.). Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East: In the Crucible of Empire. Brill. pp. 221–223, 230–233. doi:10.1163/9789004330184_015. ISBN 978-90-04-33017-7.

- ^ Bowman 1987, p. 373.

- ^ Raymond 2010, p. 222.

- ^ Josephus, Flavius (1981). The Jewish War. Translated by Williamson, G. A. Introduction by E. Mary Smallwood. New York: Penguin. p. 24.

- ^ JW preface. 3.

- ^ a b JW preface. 4.

- ^ a b c Ant. preface. 3.

- ^ Ant. preface. 4.

- ^ Feldman 1998, p. 9.

- ^ a b Feldman 1998, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Feldman 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Ehrman 1999, pp. 848–849.

- ^ "Josephus: The Life of Flavius Josephus". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-04.

- ^ Josephus. The War of the Jews.

- ^ Daniel 2:21

- ^ a b Ant. preface. 1.

- ^ Ant. preface. 2.

- ^ Feldman 1998, p. 232.

General sources[edit]

- Aune, David Edward (1991) [first published 1983]. Prophecy In Early Christianity and the Ancient Mediterranean World. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-0635-X.

- Bowman, Steven (1987). "Josephus in Byzantium". In Feldman, Louis H.; Hata, Gōhei (eds.). Josephus, Judaism and Christianity. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 90-04-08554-8.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium (Kindle ed.).[ISBN missing]

- Feldman, Louis H. (1998). Josephus's Interpretation of the Bible. Berkeley: University of California Press.[ISBN missing]

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1996). Dreams & Dream Reports in the Writings of Josephus: A Traditio-Historical Analysis. E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10616-2.

- Gray, Rebecca (1993). Prophetic Figures in Late Second Temple Jewish Palestine: The Evidence from Josephus. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507615-X.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield.[ISBN missing]

- Maier, Paul L., ed. (1999). "Appendix: Dissertation 6 (by Whiston)". The New Complete Works of Josephus. Kregel Academic. p. 1070. ISBN 978-0-8254-9692-9. Retrieved 2013-05-07.

- Mason, Steve, ed. (1998). "Should Any Wish to Enquire Further (Ant. 1.25): The Aim and Audience of Josephus's Judean Antiquities/Life". Understanding Josephus: Seven Perspectives. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.[ISBN missing]

- Mason, Steve, ed. (2000). Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary (10 vols. in 12 ed.). Leiden: Brill.[ISBN missing]

- Millard, Alan Ralph (1997). Discoveries From Bible Times: Archaeological Treasures Throw Light on The Bible. Lion Publishing. ISBN 0-7459-3740-3.

- Murphy, Catherine M. (2008). The Historical Jesus For Dummies. Wiley Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-16785-4.

- Nodet, Etienne (1997). A Search for the Origins of Judaism: From Joshua to the Mishnah. Continuum International Publishing Group.[ISBN missing]

- Raymond, Joseph (2010). Herodian Messiah: Case For Jesus As Grandson of Herod. Tower Grover Publishing. ISBN 978-0615355085.

- Schürer, Emil (1973) [1891]. Vermes, Géza; Millar, Fergus; Black, Matthew (eds.). The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C. – A.D. 135). Continuum International Publishing Group.[ISBN missing]

- Eisler, Robert (1931). The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist according to Flavius Josephus' recently rediscovered 'Capture of Jerusalem' and other Jewish and Christian sources. NY: L. MacVeagh, The Dial Press. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

Further reading[edit]

| Library resources about Josephus |

- The Works of Josephus, Complete and Unabridged New Updated Edition. Translated by Whiston, William; Peabody, A. M. (Hardcover ed.). M. A. Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8. (Josephus, Flavius (1987). The Works of Josephus, Complete and Unabridged New Updated Edition (Paperback ed.). ISBN 1-56563-167-6.)

- Hillar, Marian (2005). "Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus". Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism. Washington, DC: American Humanist Association. 13: 66–103.

- O'Rourke, P. J. (1993). "The 2000 Year Old Middle East Policy Expert". Give War A Chance. Vintage. ISBN 9780679742012.

- Pastor, Jack; Stern, Pnina; Mor, Menahem, eds. (2011). Flavius Josephus: Interpretation and History. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-19126-6. ISSN 1384-2161.

- Bilde, Per. Flavius Josephus between Jerusalem and Rome: his life, his works and their importance. Sheffield: JSOT, 1988.

- Shaye J. D. Cohen. Josephus in Galilee and Rome: his vita and development as a historian. (Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition; 8). Leiden: Brill, 1979.

- Louis Feldman. "Flavius Josephus revisited: the man, his writings, and his significance". In: Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt 21.2 (1984).

- Mason, Steve: Flavius Josephus on the Pharisees: a composition-critical study. Leiden: Brill, 1991.

- Rajak, Tessa: Josephus: the Historian and His Society. 2nd ed. London: 2002. (Oxford D.Phil. thesis, 2 vols. 1974.)

- The Josephus Trilogy, a novel by Lion Feuchtwanger

- Der jüdische Krieg (Josephus), 1932

- Die Söhne (The Jews of Rome), 1935

- Der Tag wird kommen (The day will come, Josephus and the Emperor), 1942

- Flavius Josephus Eyewitness to Rome's first-century conquest of Judea, Mireille Hadas-lebel, Macmillan 1993, Simon and Schuster 2001

- Josephus and the New Testament: Second Edition, by Steve Mason, Hendrickson Publishers, 2003.

- Making History: Josephus and Historical Method, edited by Zuleika Rodgers (Boston: Brill, 2007).

- Josephus, the Emperors, and the City of Rome: From Hostage to Historian, by William den Hollander (Boston: Brill, 2014).

- Josephus, the Bible, and History, edited by Louis H. Feldman and Gohei Hata (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1988).

- Josephus: The Man and the Historian, by H. St. John Thackeray (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1967).

- A Jew Among Romans: The Life and Legacy of Flavius Josephus, by Frederic Raphael (New York: Pantheon Books, 2013).

- A Companion to Josephus, edited by Honora Chapman and Zuleika Rodgers (Oxford, 2016).

External links[edit]

- Works

- PACE Josephus: text and resources in the Project on Ancient Cultural Engagement at York University, edited by Steve Mason.

- works by Flavius Josephus at Perseus digital library – Greek (Niese) and English (Whiston) 1895 editions

- Works by Josephus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Josephus at Internet Archive

- Works by Josephus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Works of Flavius Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (Whiston, lacks Loeb numbers)

- De bello judaico digitized codex (1475) at Somni

- Lecture, Dr. Henry Abramson (historian): Josephus: First-Person Accounts of Jewish History on YouTube, June 2020.

- Other

- The AHRC Reception of Josephus in Jewish Culture Project and Josephus Reception Archive

- Josephus.org, G. J. Goldberg

- Flavius Josephus The Jewish History Resource Center – Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Flavius Josephus, Judaea and Rome: A Question of Context

- Flavius Josephus at livius.org

- Josephus

- 1st-century historians

- 1st-century Jews

- 1st-century Romans

- 1st-century writers

- 37 births

- Ancient Roman antiquarians

- Greco-Roman military writers

- Hellenistic Jewish writers

- Hellenistic Jews

- Jewish apologists

- Jewish historians

- Jewish Roman (city) history

- Judean people

- Roman-era Greek historians

- Historians of Phoenicia

- People from Jerusalem